Between 1999 And 2010, How Has Primary School Enrollment In Developing Regions Changed?

This is a 'meta-entry' on teaching. The visualizations and research discussed here are also discussed in other, more specific information entries. These include:

- Financing Pedagogy,

- Primary Education,

- Higher Instruction,

- Education Skill Premium .

Pedagogy is widely accepted to be a fundamental resource, both for individuals and societies. Indeed, in most countries bones educational activity is nowadays perceived not simply as a right, but also as a duty – governments are typically expected to ensure access to basic didactics, while citizens are ofttimes required past law to reach educational activity up to a sure basic level.i

In this entry we begin by providing an overview of long run changes in education outcomes and outputs across the world, focusing both on quantity and quality measures of education attainment; and so provide an analysis of available evidence on the determinants and consequences of educational activity.

From a historical perspective, the globe went through a great expansion in teaching over the past 2 centuries. This can be seen across all quantity measures. Global literacy rates have been climbing over the course of the concluding ii centuries, mainly though increasing rates of enrollment in master education. Secondary and tertiary instruction have as well seen desperate growth, with global average years of schooling being much higher now than a hundred years ago. Despite all these worldwide improvements, some countries accept been lagging behind, mainly in sub-Saharan Africa, where there are still countries that have literacy rates below 50% among the youth.

Information on the production of pedagogy shows that schooling tends to be largely financed with public resources across the earth, although a bully deal of heterogeneity is observed between countries and world regions. Since differences in national expenditure on education practice non explicate well cantankerous-country differences in learning outcomes, the data suggests that generic policies that increase expenditure on standard inputs, such as the number of teachers, are unlikely to exist effective to amend education outcomes.

Regarding the consequences of education, a growing body of empirical research suggests that better education yields higher individual income and contributes towards the construction of social capital and long-term economic growth.

All our charts on Global Education

Literacy

Context

Literacy is a key skill and a key measure of a population's pedagogy. UNESCO operationalizes the measurement of literacy every bit the ability to both read and write a brusk, simple statement about one's own life. Literacy rates are determined by literacy questions in a demography or sample survey of a population, in standardized tests of literacy, or via extrapolation from statistics almost school enrollment and educational attainment.2

Statistics of literacy rates for recent decades are published by statistical offices. For before periods, historians accept to reconstruct information from other sources. The almost common method is to calculate the share of those people who could sign official documents (e.g. courtroom documents).

Our entry on Literacy contains further in-depth information on the topic.

How has global literacy evolved in the terminal 2 centuries?

While the primeval forms of written communication engagement back to most 3,500-three,000 BCE, literacy remained for centuries a very restricted technology closely associated with the exercise of power. It was only until the Middle Ages that book production started growing and literacy among the general population slowly started becoming important in the Western World.3

In fact, while the ambition of universal literacy in Europe was a fundamental reform born from the Enlightment, it took centuries for it to happen. Fifty-fifty in early-industrialized countries it was but in the 19th and 20th centuries that rates of literacy approached universality.

The visualization presents estimates of world literacy for the period 1800-2014. As nosotros can run across, literacy rates grew constantly only rather slowly until the showtime of the twentieth century. And the charge per unit of growth actually climbed after the middle of the 20th century, when the expansion of basic teaching became a global priority. You tin can read more well-nigh the expansion of education systems around the world in our entry on Financing Education.

How is literacy distributed across the world?

The interactive map shows literacy rates around the world, using recent estimates published in the CIA Factbook. As it tin can be seen, all countries outside Africa (with the exception of Afghanistan) take literacy rates higher up fifty%.

Despite progress in the long run, however, large inequalities remain, notably between sub-Saharan Africa and the rest of the earth. In Burkina Faso, Niger and South Sudan – the African countries at the bottom of the rank – literacy rates are withal beneath 30%.

How fast are we closing cross-state inequalities in literacy?

The preceding visualization shows that, despite the fact that literacy is today higher than ever, there are nevertheless important challenges in many developing countries. However, data on literacy rates by age groups shows that in most countries, and certainly in virtually all developing countries, there are large generational gaps: younger generations are progressively better educated than older generations. This indicates that in these countries the literacy charge per unit for the overall population will continue to increase.

The visualization shows the estimates and projections of the share of individuals, across countries, who have no education. These figures, from The International Plant for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA), advise that we should see rates of education increasing equally the world develops – and past 2050, merely five countries are likely to accept a rate of no education above twenty%: these are Burkina Faso, Ethiopia, Guinea, Mali and Niger.

While these projections entail a number of assumptions, the conclusion seems to exist that by 2050 we can hope virtually of the cross-state gaps in literacy to be closed.

School enrollment and attendance

Context

School enrollment and attendance are ii important measures of educational attainment. Hither we focus on enrollment and attendance rates specifically at the primary level.

The charge per unit of primary schoolhouse enrollment is typically measured through administrative data, and is defined every bit the number of children enrolled in primary school who belong to the historic period grouping that officially corresponds to primary schooling, divided by the full population of the aforementioned historic period group.

The rate of attendance, on the other hand, is typically measured through household survey data, and is defined as the percent of children in the age group that officially corresponds to master schooling who are reported as attending master schoolhouse.

Primary school enrollment around the world increased drastically in the last century

The visualization shows estimates of primary educational activity enrollment rates for a choice of 111 countries during the menstruation 1870-2010. Y'all tin can add countries, or switch to the 'map' view, past selecting the corresponding options at the top of the nautical chart.

The plotted series for the UK typifies the experience of early-industrialized countries, where enrollment in chief education grew rapidly with the spread of compulsory chief schooling in the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

And the instance of Colombia is representative of the design observed across many developing countries, where chief pedagogy enrollment rates grew peculiarly fast in the 2d one-half of the 20th century.

The growth in admission to primary education across developing countries was achieved through an important increase in government expenditure on education in these countries (you tin can read more than virtually this in our discussion of global expansion in education expenditure).

Primary school attendance remains a claiming in many developing countries

The previous visualization showed the of import progress that countries effectually the world have made regarding admission to education, as measured by enrollment rates. Hither nosotros focus on evidence of admission to educational activity, as measured by school attendance. The divergence lies in the source of information regarding participation: enrollment figures come from official records, while omnipresence estimates comes from asking households direct.

In the majority of developing countries, cyberspace enrollment rates are higher than attendance rates. This reflects the fact that many children who are officially enrolled, practise not regularly attend school. The visualization, from the UNESCO report Measuring Exclusion From Primary Education (2005), shows the relationship between these 2 measures. The source reports that "amid the 59 countries with comparable data, in 24 countries participation rates drop by five percentage points for the primary school-age group when household surveys are used instead of administrative data."4

The interactive map shows contempo main school attendance estimates for a selection of (mainly) low and middle income countries in Africa, where the gaps between attendance and enrollment are largest. Every bit we can see, low attendance rates are an important problem in sub-Saharan Africa – more so than enrollment figures advise. In Niger, Chad and Republic of liberia, estimates propose that less than half of the school-aged children attend chief school.

Out-of-school children

The nautical chart shows the number of the world's young population who are out of school across principal- and secondary-school-age. For 1998 information technology is estimated that 381 million children were out of school. Until 2014 this number cruel to 263 million, despite an increase in the global immature population.

For 2014 information technology can exist seen that at the chief school age the number of girls that are out of school is college than for boys. At the secondary school age the contrary is true, more than boys than girls are out of secondary school.

Years of schooling

Context

The average number of years spent in school are another common measure of a population's didactics level. It is a helpful measure, because it allows aggregation of attainment beyond teaching levels. This allows an analysis of the 'stock of human capital' that a population has at any given point in time.

Average, or hateful years of schooling of a population, are typically calculated from data on (i) the distribution of the population by age group and highest level of education attained in a given yr; and (ii) the official duration of each level of educational activity.

The world is more than educated than e'er before

In the previous section we showed, through school enrollment data, that the world went through a great expansion in pedagogy over the past ii centuries. Here we show evidence of this process of teaching expansion using cross-land estimates of average years of schooling.

The interactive visualization shows trends in years of schooling for a selection of 111 countries during the period 1870-2017. As usual, you lot can add countries, or switch to the 'map' view, past selecting the corresponding options at the meridian of the chart. As nosotros tin see, the average number of years spent in schoolhouse has gone up around the globe. And once again, we meet the pattern that has already been discussed: early-industrialized countries pioneered the expansion of didactics in the 19th century, simply this process became a global phenomenon later on the second World State of war.

The experience of some countries, such every bit Republic of korea, shows how remarkably apace educational attainment can increase.

To emphasize the points above, here we see a map which shows the evolution of hateful years of schooling across the globe, using a related, only different source. Specifically, these estimates come up from Barro Lee (2010)6, and comprehend the menses 1950-2010.

The rise in mean years of schooling is consistently observed in both Barro Lee (2010) and Lee & Lee (2016). It is the result of increased appreciation of the benefits of instruction to the individual and gild, likewise as and increased government provision.

How has the stock of human majuscule evolved in the long run?

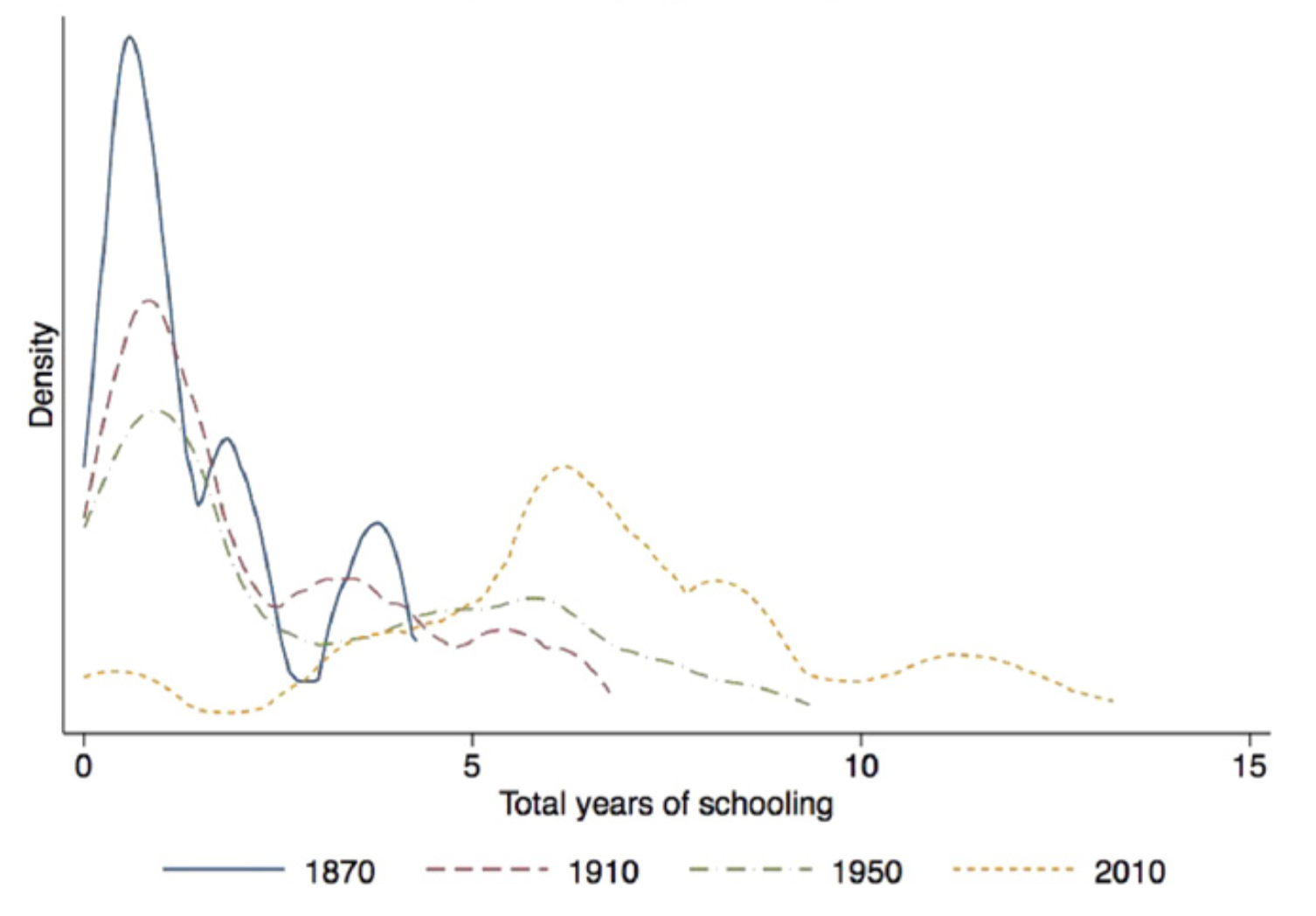

In the previous interactive visualisation we showed how the average number of years spent in schoolhouse has been going up constantly across the world. Here we go further and explore changes beyond the entire global distribution of years of schooling.

The graph, from Lee and Lee (2016)7, plots the distribution of the number of years of schooling across the entire adult population, for selected years. Roughly speaking, you can think of this graph as a 'smoothen histogram': if all people in the earth were ranked past years of education, this chart would approximately tell the states, for any number of years in the horizontal axis, the proportion of the earth population that accomplished those years.8

We can see that in 1870, the distribution was concentrated at the left: most of the people had between 0 and 3 years of education. In dissimilarity, by 2010 the distribution had shifted drastically to the correct.

We can see that there has been a continuous rightward shift in the successive distributions of schooling across time. This reflects the fact that there has been a continuous increase in average years of schooling worldwide: as the share of the uneducated population brutal over time, the concentration at the lower level became less pronounced.

The increasingly long tails that nosotros see in the distributions, are the result of cross-country inequalities in pedagogy expansion – in the long run, we can see that there has been a considerable increase in the dispersion of the years of schooling. This is mainly the result of cross-country differences, since some nations started expanding education much later than other, and some are still lagging behind. Interestingly, however, inequality grew in the menstruation 1870-1950, but later this signal, it has slowly started going down (discover that the distribution in 2010 is 'bulkier' in the middle, vis-a-vis the distribution in 1950). Below nosotros provide more detailed evidence of how teaching inequality has been going downward since 1950.

Globe distribution of years of schooling for selected years – Figure 7B in Lee and Lee (2016)9

School life expectancy captures the years of schooling children can expect

The number of years of schooling that a kid of school entrance age can expect to receive if the current age-specific enrollment rates persist throughout the child's life by country.

This is shown in the map.

What has been the evolution of gender inequalities in education?

The visualization shows the evolution of female-to-male ratios of educational attainment (mean years of schooling) across different world regions.

The estimates in the visualization represent to regional averages of total yr of schooling for females (15-64 years of age), divided past the corresponding regional averages for males (fifteen-64 years of age). Regional averages are population-weighted.

Back in 1870 women in the 'advanced economies'10 had only 0.75 years for every year of education that men had. And in other regions it was fifty-fifty much unequal than that, in Sub-Sahran Africa women had but 0.08 years of instruction for every yr of educational activity that men received.

Since and then there has generally been a strong upward tendency in the gender ratios across all world regions, which indicates that the inequality between men and women in access to teaching has been declining. In fact, Latin America and Eastern Europe caught up with the group of 'advanced economies' in the 1980s, and the gender gaps in these regions have already been airtight most completely (i.due east. the gender ratios approximate the 100% benchmark for education gender parity).

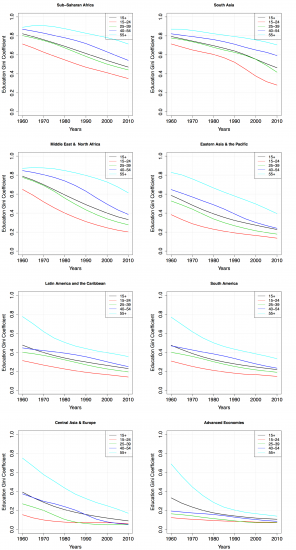

How has education inequality changed in the last couple of decades?

The visualization shows the recent evolution of inequality in educational attainment, through a serial of graphs plotting changes in the Gini coefficient of the distribution of years of schooling across different earth regions. The Gini coefficient is a measure of inequality and college values indicate higher inequality – yous can read most the definition and estimation of Gini coefficients in our entry on income inequality. The fourth dimension-series chart shows inequality past historic period group. It can be seen that equally inequality is falling over time, the level of inequality is higher for older generations than it is for younger generations. We can also come across that in the flow 1960-2010, education inequality went down every year, for all age groups and in all globe regions.

Have gains from historical education expansion fully materialized? The breakdown past age gives us a view into the futurity: equally the inequality is lower among today'due south younger generations, we tin expect the decline of inequality to continue in the future. Thus, further reductions in education inequality are even so to be expected within developing countries; and if the expansion of global education tin be continued, we can speed upwards this of import process of global convergence.

Education Gini coefficients by earth region for selected age groups, 1960- 2010 – Figure iv in Crespo Cuaresma et al. (2013)xi

Attainment by level

Context

The highest level of education that individuals complete is another common mensurate of educational attainment. This measure is used as an input to calculating years of schooling, and allows clear comparisons across levels of teaching.

The estimates discussed in this department come from The International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA). These include both historic estimates and projections. You can read more than about this source of data, including details on the estimation methodology, in our entry on Projections of Future Teaching.

Didactics at college levels, mainly secondary and tertiary, is becoming increasingly important around the world

A global picture of attainment shows estimates and projections of the total world population by level of instruction. Information technology shows that our world will exist inhabited past more and more educated people: while in 1970 there were just around 700 million people in the world with secondary or postal service-secondary education, by 2100 this figure is predicted to be ten times larger.

Learning outcomes

Context

Throughout this entry we have discussed 'quantity' measures of educational attainment. Now nosotros turn to 'quality' measures of education.

Measuring learning outcomes in a way that enables us to make comparisons across countries and time is difficult. There are several international standardised tests that try to measure learning outcomes in a systematic style across countries; but these tests are relatively new, and they tend to encompass only specific geographical areas and skills.

One possible approach to learn from all these overlapping but disparate international and regional tests, is to put them on a consistent calibration, and then pool them together across skills to maximize coverage across years and countries. This is exactly what Nadir Altinok, Noam Angrist and Harry Patrinos did in a new working paper: Global Data Assault Instruction Quality (1965–2015). They collected data from a large fix of psychometrically-robust international and regional student achievement tests available since 1965, and they linked them together in a mutual measurement system.

Hither nosotros show some key charts using their data. Y'all tin read more nigh their approach and results in our blog post "Global education quality in 4 charts".

A comparing of learning outcomes, country by country

This nautical chart plots Gross domestic product per capita (after adjusting for differences in prices beyond countries and time), confronting average pupil test scores (after homogenizing and pooling international and regional student assessments beyond teaching levels and subjects). Each bubble in this chart is a land, where colours represent regions and bubble sizes denote population.

Equally we tin see, learning outcomes tend to be much higher in richer countries; only differences beyond countries are very big, fifty-fifty amid countries with similar income per capita.

The evolution of learning outcomes over fourth dimension

This scatter plot compares national boilerplate learning outcomes in 1985 and 2015 (or closest years with available data).

Amongst these countries we meet a broad positive trend: Most bubbles are above the diagonal line, which means the bulk of countries have seen improvements in learning outcomes over the last couple of decades. This is a neat accomplishment! It shows that policies matter and learning outcomes can, and frequently do meliorate.

The error margin on these differences is ofttimes large, so small deviations from the diagonal line are not pregnant.

But it is worrying that many low-performing countries are substantially below the diagonal line. Consider the comparison between Chile and Burkina Faso in the center of the nautical chart: Both countries had similar average scores a couple of decades agone, but while Chile has improved, Burkina Faso has regressed.

Y'all can check country by country trends over fourth dimension in this line chart.

Pupil achievement beyond average scores

This chart shows the share of students who attain minimum proficiency (i.east. the proportion who pass a global benchmark for minimum skills), against the share who achieve avant-garde proficiency (i.due east. the proportion who pass a global benchmark for advanced skills).

Here we see that those countries where a larger share of students accomplish minimum proficiency, tend to also be countries where a larger share of students attain avant-garde proficiency. Amend education lifts all boats.

Depression-income, depression-performing countries are clustered at the bottom of the global scale: the distribution of test scores within these countries is shifted down, relative to high-performing countries. The challenges are therefore much larger in these countries. Less than half of students in Sub-Saharan Africa reach the minimum global threshold of proficiency; and very, very few students accomplish advanced skills.

Rich countries, on the other hand, tend to be less clustered. For case, Belgium and Canada take roughly similar average outcomes; just Canada has a higher share of students that achieve minimum proficiency, while Kingdom of belgium has a larger share of students who achieve advanced proficiency. This shows that there is pregnant data that boilerplate scores fail to capture. The implication is that it's non plenty to focus on average outcomes to assess challenges in didactics quality.

Y'all can compare achievement higher up minimum, intermediate, and advanced benchmarks, country by country and over time, in these three line charts:

- Share of students achieving minimum learning outcomes

- Share of students achieving intermediate learning outcomes

- Share of students achieving advanced learning outcomes

Context

The most common way to judge differences in the way countries 'produce' pedagogy, is to clarify data on expenditure.

In this section we begin by providing an overview of didactics expenditure effectually the world, and then plow to the question of how expenditure contributes to the production of education.

The chief source of data on international education expenditure is UNESCO's Found for Statistics (UIS). The same data is also then published by the World Depository financial institution (World Banking company EdStats and Earth Development Indicators) and Gapminder. It is also the main source of educational activity data for most UN reports – such equally the EFA Global Monitoring Study (UNESCO), the Human Development Report (UNDP), the State of the World's Children written report (UNICEF) and the Millennium Evolution Goals (UN).

Further in-depth information on this topic, including definitions, data sources, historical trends and much more, can be found in our dedicated entry Financing Instruction.

Cantankerous-land spending patters

When did the provision of education showtime go a public policy priority?

Governments around the world are present widely perceived to be responsible for ensuring the provision of attainable quality education. The advancement of the idea to provide didactics for more and more children only began in the mid 19th century, when well-nigh of today'south industrialized countries started expanding primary educational activity.

The visualization, plotting public expenditure on education as a share of Gross Domestic Product (Gdp) for a number of early-industrialized countries, shows that this expansion took identify mainly through public funding.12

Chief education continues to be publicly funded in industrialized countries

Those countries that pioneered the expansion of principal education in the 19th century – all of which are current OECD member states – relied heavily on public funding to do so. Today, public resources still dominate funding for the main, secondary and postal service-secondary non-3rd instruction levels in these countries.

While in the last decade the share of public funding for these levels of education has decreased slightly, the broad blueprint is remarkably stable. The visualization presents OECD-average expenditure on education institutions past source of funds.13

The world is expanding funding for education today

The terminal two decades have seen a small but full general increment in the share of income that countries devote to pedagogy. The chart plots trends in public expenditure on instruction as a share of Gross domestic product. Every bit usual, a selection of countries is shown past default, but other countries can be added by clicking on the relevant pick at the top of the chart. Although the data is highly irregular due to missing observations for many countries, we can still observe a broad up trend for the majority of countries. Specifically, it tin can exist checked that of the 88 countries with available data for 2000/2010, three-fourths increased education spending as a share of Gross domestic product within this decade. Every bit incomes – measured past GDP per capita – are mostly increasing around the world, this ways that the full amount of global resources spent on education is also increasing in absolute terms.

The visualization shows the percentage of full education expenditures contributed straight by households in xv loftier income countries and 15 depression/center income countries (most recent data available on 2014).

The height nautical chart in this figure, corresponding to high income countries, shows a very clear pattern: households contribute the largest share of expenses in third pedagogy, and the smallest share in primary education. Roughly speaking, this blueprint tends to be progressive, since students from wealthier households are more likely to attend third teaching, and those individuals who attend third education are likely to perceive large individual benefits.fourteen In contrast, the lesser chart shows a very unlike picture: in several depression-income countries households contribute proportionally more than to primary education than to higher levels. Malawi is a notable instance in betoken – tertiary didactics is well-nigh completely subsidised by the land, withal household contribute with almost 20% of the costs in primary educational activity. Such distribution of private household contributions to instruction is regressive.

The link between expenditure and outcomes

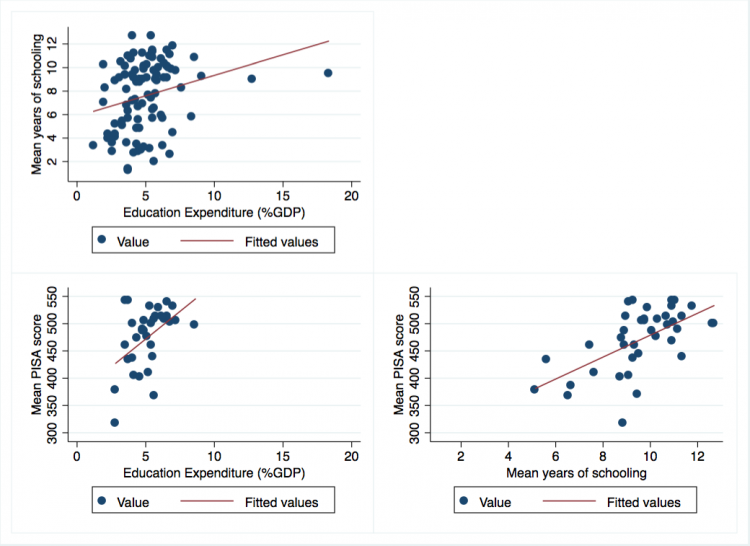

Do countries that spend more than public resource on pedagogy tend to have ameliorate education outcomes?

The visualization presents three scatter plots using 2010 data to show the cross-country correlation between (i) pedagogy expenditure (equally a share of GDP), (ii) mean years of schooling, and (iii) mean PISA test scores. At a cross-sectional level, expenditure on instruction correlates positively with both quantity and quality measures; and non surprisingly, the quality and quantity measures as well correlate positively with each-other. Only correlation does non imply causation: there are many factors that simultaneously impact education spending and outcomes. Indeed, these scatterplots show that despite the broad positive correlation, there is substantial dispersion abroad from the trend line – in other words, at that place is substantial variation in outcomes that does not seem to exist captured by differences in expenditure.

Correlation between education outcomes and teaching expenditure (2010 data)fifteen

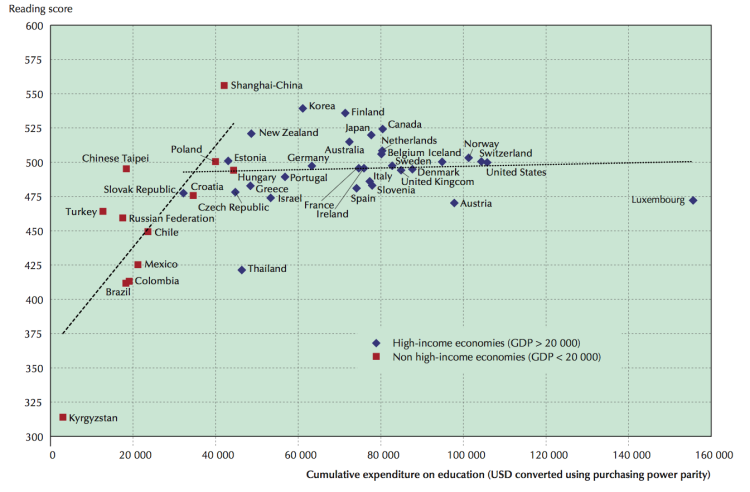

Does cross-land variation in government education expenditure explain cantankerous-country differences in education outcomes?

The visualization presents the relationship between PISA reading outcomes and average education spending per student, splitting the sample of countries by income levels. Information technology shows that income is an important cistron that affects both expenditure on education and teaching outcomes: we tin see that above a certain national income level, the relationship betwixt PISA scores and education expenditure per pupil becomes virtually inexistent. Several studies with more sophisticated econometric models corroborate the fact that expenditure on pedagogy does not explain well cross-country differences in learning outcomes.xvi You can read more than about test scores and learning outcomes in our entry on Quality of Education.

Average reading operation in PISA and average spending per student from the historic period of 6 to 15 – Effigy 1 in OECD (2012)17

What inputs enter the 'education production function'?

The fact that expenditure on education does not explicate well cantankerous-country differences in learning outcomes is indicative of the intricate nature of the procedure through which such outcomes are produced. The 'production function' provides a conceptual framework to think about the determinants of learning outcomes18:

where A is skills learned (accomplishment), s is years of schooling, Q is a vector of school and teacher characteristics (quality), C is a vector of child characteristics (including "innate ability"), H is a vector of household characteristics, and I is a vector of school inputs nether the control of households, such as children'due south daily attendance, effort in schoolhouse and in doing homework, and purchases of school supplies.

This conceptualization highlights that, for any given level of expenditure, the output achieved will depend on the input mix. And consequently, this implies that in order to explain education outcomes, nosotros must rely on information about specific inputs.

Available bear witness specifically on the importance of schoolhouse inputs, suggests that learning outcomes may be more sensitive to improvements in the quality of teachers, than to improvements in course sizes. And regarding household inputs, the recent experimental show suggests that interventions that increase the benefits of attention school (e.one thousand. conditional cash transfers) are especially likely to increase pupil time in school; and that those that incentivise academic attempt (e.g. scholarships) are likely to improve learning outcomes.

Policy experiments have as well shown that pre-school investment in demand-side inputs leads to large positive impacts on education – and other important outcomes later in life. The environment that children are exposed to early on in life, plays a crucial part in shaping their abilities, behavior and talents.

Context

Education is a valuable investment, both individually and collectively. Here nosotros analyse available evidence of the individual (i.e. individual) and social (i.eastward. collective) returns to education.

The most common mode to mensurate the private returns to education, is to study how attainment improves private labor market outcomes – usually past attempting to measure the effect of teaching on wages. Regarding social returns, the most mutual approach is to measure out the effect of educational activity on pro-social behaviour (e.m. volunteering, political participation, interpersonal trust) and economic growth.

Most of the evidence presented below is 'descriptive', in the sense that it points towards correlations between education and diverse individuals and social outcomes, without necessarily proving causation. In each case, we provide a word of the robustness of the bear witness.

Private returns to didactics

How do earnings correlate with education?

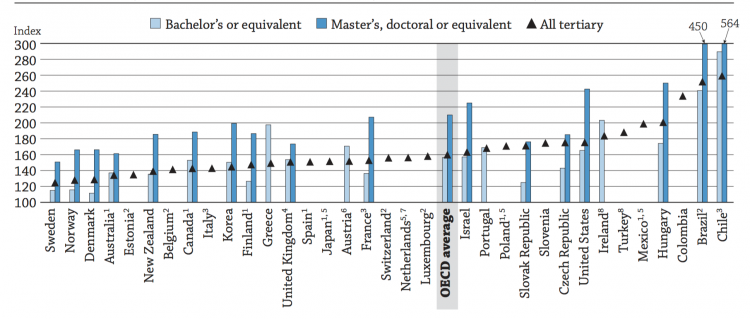

The OECD's study Didactics at a Glance (2015) provides descriptive show of the link betwixt individual education and income. The chart shows the earnings of tertiary-educated workers, by level of 3rd didactics, relative to the earnings of workers with upper secondary pedagogy. As we can encounter, in all OECD countries for which information is available, the higher the level of education, the greater the relative earnings.

The countries in this chart are ordered in ascending club of relative earnings. As we tin can come across, the countries with the greatest returns to third teaching (Brazil, Chile and Colombia) are also those where 3rd education is less prevalent amongst the adult population. This is indicative of the demand-and-supply dynamics that contribute to decide wage differentials across different countries.

These figures are simply correlations, and cannot exist interpreted causally: individuas with more education are different in many ways to individuals with less education, and so we cannot aspect wage differences solely to education choices.

Is there a causal issue of education on earnings?

The previous graph gave a cross-state comparison of earning by teaching level. As pointed out, those figures were difficult to translate causally, considering they failed to account for important underlying differences in things like hours worked, experience profiles, etc.

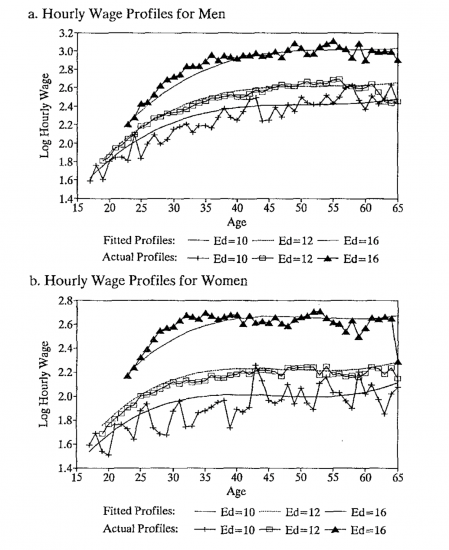

The visualization, from Menu (1999)20, attempts to pin downwardly the relationship between education and earnings, by comparing wages across education levels, genders and age groups. The data used for this figure comes from the March Current Population Surveys in the US. Educational activity levels correspond to individuals with x, 12 and 16 years of teaching. The marks show averages for each corresponding group, and the smooth lines show the predictions made by a simple econometric model explaining wages by didactics and experience.

The first conclusion from this charts is that for both genders, at any given historic period, individuals with more education receive higher wages. Moreover, these estimates suggest that the incremental benefit from boosted didactics grows with experience: the differences in wages between people with varying degrees of instruction become larger equally they advance in their careers. In other words, didactics pay-offs are not constant over the life cycle. Other studies using different data accept plant similar results (encounter, for instance, Blundell et al. 201321)

These estimates can still not exist interpreted causally, because there are yet other potential sources of bias that are unaccounted for, such equally innate ability. To address this event, the economics literature has developed different strategies. For example, past contrasting the wages of genetically identical twins with different schooling level, researchers take constitute a way of decision-making for unobservable characteristics such every bit family background and innate ability. The conclusion from these 'twin studies' is that the average estimates suggested by the figure, are not very different to those that would be obtained from more sophisticated models that control for power. In other words, there is robust evidence supporting the causal issue of educational activity on wages (for more than details come across Card 1999).

Social returns to educational activity

Educational activity correlates with prosocial behavior

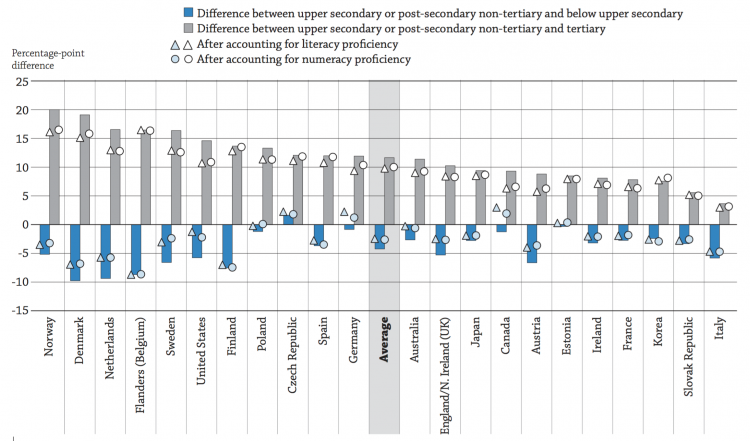

The nautical chart uses OECD results from the Survey of Adult Skills to bear witness how cocky-reported trust in others correlates with educational attainment. More precisely, this chart plots the percentage-point departure in the likelihood of reporting to trust others, past education level of respondents. Those individuals with upper secondary or post-secondary non-tertiary education are taken as the reference group, so the pct point divergence is expressed in relation to this group.

As nosotros tin can see, in all countries those individuals with tertiary education were past far the group well-nigh likely to report trusting others. And in almost every country, those with postal service-secondary non-tertiary education were more likely to trust others than those with primary or lower secondary education. The OECD's report Teaching at a Glance (2015) provides similar descriptive evidence for other social outcomes. The report concludes that adults with higher qualifications are more probable to written report desirable social outcomes, including skilful or excellent health, participation in volunteer activities, interpersonal trust, and political efficacy. And these results hold afterward decision-making for literacy, gender, historic period and monthly earnings.

Equally usual, correlation does not imply causation – just it does testify an important pattern that supports the idea that education is indeed necessary to produce social capital.

Countries with higher educational attainment in the past are more likely to accept democratic political regimes today

A long-standing theory in political scientific discipline stipulates that a country's level of education attainment is a cardinal determinant of the emergence and sustainability of autonomous political institutions, both because it promotes political participation at the private level, and considering it fosters a commonage sense of civic duty.

Under this hypothesis, therefore, we should expect that didactics levels in a state correlate positively with measures of democratisation in subsequent years. The visualization shows that this positive correlation is indeed supported by the data. As we tin run into, countries where adults had a higher boilerplate education level in 1970, also have more democratic political regimes today (you can read more almost political regimes in our entry on Republic).

As usual, these results should be interpreted carefully, considering they do not imply a causal link: information technology does not prove that increasing education necessarily produces democratic outcomes everywhere in the globe.

However, the academic enquiry here does suggest that at that place is a causal link between education and democratization – indeed, a number of empirical academic papers have found that this positive human relationship remains subsequently controlling for many other country characteristics (see, for example, Lutz, Crespo-Cuaresma, and Abbasi‐Shavazi 201024).

Women's didactics is inversely correlated with child mortality

An of import body of literature stipulates that women's education leads to lower child mortality because it contributes towards healthier habits and choices, including child spacing (run across Brown and Barrett 1991 for a more detailed conceptualization of the mechanisms).25

The visualization shows the stiff cross-land correlation between child bloodshed and educational attainment.

Educational activity outcomes predict economical growth

The economic science literature has long studied whether the level of education in a country is a determinant of economic growth. This question is motivated by the notion that amass instruction ('human capital letter') generates positive spill-over effects for anybody. A classic instance of a mechanism though which education may yield such positive economic externalities, is that aggregate education improves a country'south ability to innovate, likewise as imitate and conform new technologies, hence enabling 'technological progress' and sustained growth (see Lindahl and Krueger (2001) for an overview of farther macroeconomic theories of education and growth).26

While early studies found that schooling levels were poor predictors of economic growth, more recent studies – that crucially made apply of improve data – ostend the expected positive link. Lutz, Creso Cuaresma, and Sanderson (2008)27 conclude that "better education does not only lead to higher individual income, just also is a necessary (although not always sufficient) precondition for long-term economic growth."

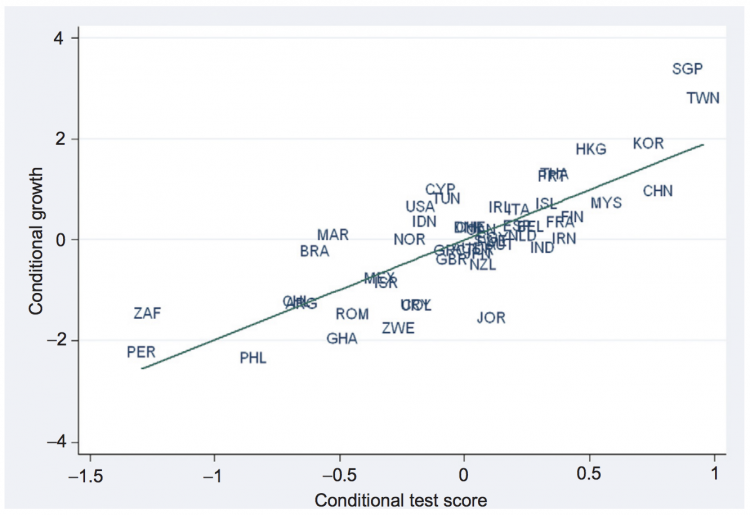

The plot, from Hanushek and Woessmann (2010),28 provides a basic representation of the association between examination scores and economic growth using data over the period 1960 to 2000. This type of graph, called a 'partial regression plot', shows the relationship betwixt exam scores and growth after accounting for the initial level of GDP per capita and for years of schooling in 1960. As we can see, there is a strong positive relationship. What we learn from this upshot is that "test scores that are larger by 1 standard difference (measured at the educatee level across all OECD countries in PISA) are associated with an average annual growth charge per unit in GDP per capita that is two percentage points higher over the whole 40-year period."29

This coincides with other studies showing that historical increases in the number of universities across countries are positively associated with subsequent growth of GDP per capita (Valero and Van Reenen 2016).30

A number of studies have found that information technology is actually education in the form of cerebral skills, rather than mere school attainment, what really matters for predicting individual earnings and economic growth. You tin can read more about this in Delgado, Henderson and Parmeter (2014)31, Hanushek (2013)32 and Pritchett (2001).33

Data sources

There are 2 of import sources of long-run cross-country data on teaching attainment. The well-nigh recent one is Lee and Lee (2016).35 These estimates rely on a variety of historical sources, and expand existing estimates from previous studies past using a significant number of new demography observations. The authors relied on information near the years of institution of the oldest schools at unlike didactics levels in private countries, in order to suit their estimates; and they also used information on repetition ratios to adjust for school repeaters.

The other main source on this topic are the estimates from the International Found for Practical Systems Analysis (IIASA) and the Vienna Establish of Demography (VID). These institutions reconstructed educational attainment distributions past historic period and sex for 120 countries for the years 1970–2000. These estimates correspond to 'back projections': researchers used educational attainment estimates from the UN for the year 2000, and projected backwards from this single year. You can read more near this source of data and the underlying methodology in our entry on Education Projections.

You find more research, data visualisations, and detailed lists of data sources in the more specific entries:

- Financing Pedagogy

- Primary Education

- Higher Pedagogy

- Instruction Skill Premium

Source: https://ourworldindata.org/global-education

Posted by: knappspass1986.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Between 1999 And 2010, How Has Primary School Enrollment In Developing Regions Changed?"

Post a Comment